Burkina Faso Sovereignty Semiotics: Revolution Without Reform

Burkina Faso sovereignty has become a powerful case study in the semiotics of sovereignty—how power is represented, narrated, and embodied. Since the 2014 uprising that toppled Blaise Compaoré, the nation has witnessed a shift from revolutionary energy to symbolic governance. The question remains: has anything truly changed, or is this just revolution without reform?

1. The 2014 Uprising: A Constitutional Coup from Below

Burkina Faso In October 2014, Burkina Faso erupted in protest as President Blaise Compaoré attempted to extend his 27-year rule. What followed was a youth-led mass mobilization that succeeded in ousting him. Protesters called it a “constitutional coup”—a play on words that reframed elite manipulation of law as theft of sovereignty, and citizen resistance as the rightful reclamation of power.

Burkina Faso This was the beginning of a new semiotic regime—where language, images, and gestures of power took center stage. Graffiti, hashtags, slogans, and symbols were tools of resistance. Youth wore military fatigues in defiance. Banners evoked Thomas Sankara, the slain revolutionary leader of the 1980s. The streets became a canvas for an insurgent grammar of sovereignty.

2. Relative Deprivation and Generational Discontent

The uprising wasn’t just about a president overstaying his welcome. It reflected deep generational frustration. Young Burkinabè, connected to the world via digital platforms, were increasingly aware of their marginalization. They experienced what sociologists call relative deprivation: knowing what rights and opportunities should be available, but seeing them withheld by a gerontocratic elite.

In response, the youth claimed both the streets and the narrative. “Too young to remember another president” became a rallying cry. They weren’t simply asking for new leaders—they were demanding a new logic of leadership. This was a call for sovereignty reimagined.

3. The Semiotics of Resistance: Images, Gestures, and Icons

The semiotics of resistance manifested in powerful ways. Thomas Sankara’s image re-emerged everywhere—from street murals to t-shirts to WhatsApp profile pictures. Activists consciously adopted visual cues of the Sankarist era: military dress, Pan-African rhetoric, and symbols of anti-imperialism. These were not nostalgia—they were strategic signs, encoding an alternative vision of statehood.

Even social media contributed to the new semiotic order. Hashtags such as #BalaiCitoyen (Citizen Broom) became more than slogans—they were symbols of cleanliness, justice, and civic power. Protest wasn’t only political; it was semiotic.

4. From Resistance to Power: The Rise of Symbolic Governance

Over the next decade, the language of the revolution became state language. When Ibrahim Traoré, a young military officer, took power in 2022, he adopted the style and symbols of revolutionary legitimacy. His public image was crafted through Sankarist aesthetics: combat attire, anti-French speeches, and pledges of Pan-African solidarity.

He removed French troops, restructured alliances toward Russia and Turkey, and erected a new statue of Sankara. Yet, despite this revolutionary imagery, many of the structures of governance remained unchanged: youth exclusion, centralized authority, and limited press freedom. The revolution had become a branding strategy.

5. Semiotics of Sovereignty in a Post-Colonial State

The case of Burkina Faso reflects a broader African trend: semiotics replacing substance. Leaders perform sovereignty through symbols—flags, uniforms, nationalistic discourse—while avoiding deep reform. Announcing the exit of foreign troops becomes a performance of decolonization, even as violence, poverty, and governance crises persist.

This raises the question: what does it mean to be sovereign? Is sovereignty merely the absence of external troops, or does it require functioning institutions, equity, and agency for all citizens?

6. Discursive Substitution: Language Over Change

What we are witnessing is a phenomenon scholars call discursive substitution. Instead of enacting reforms, regimes substitute them with revolutionary language. They speak the language of justice, but don’t redistribute power. They wear the symbols of anti-colonial resistance, but replicate the authoritarianism of the past.

This dynamic has allowed states to convert dissent into state ideology. By absorbing the revolutionary discourse, the state neutralizes its radical edge while retaining its emotional appeal. The result is revolution without reform.

7. The Symbolic Regime and Youth Co-optation

Burkina Faso is now governed by what could be called a symbolic regime: a system where authority is maintained through semiotic mastery. Instead of accountability and transformation, leaders offer compelling performances of nationalism. But beneath the surface, the old power structures endure.

Youth, once at the forefront of the revolution, are now either co-opted or marginalized. The state borrows their language but denies them agency. Their demands for representation have been replaced by images of representation. They are seen, but not heard.

8. Revolution Without Reform: A Regional Pattern

This pattern is not unique to Burkina Faso. Across West Africa—in Mali, Guinea, and even parts of Sudan—we see similar dynamics: military regimes use revolutionary imagery to legitimize power, often in opposition to foreign influence. Yet structural injustices remain, and public discontent simmers beneath the surface.

Revolution becomes an aesthetic, not a project. It becomes something to perform rather than something to build. This is the paradox of contemporary African sovereignty: abundant symbols, absent substance.

9. Toward Semiotic Literacy: Seeing Beyond the Symbols

If the semiotics of sovereignty are being weaponized, then citizens need semiotic literacy—the ability to decode the difference between genuine empowerment and its performance. Protesters and scholars alike must ask: what lies behind the rhetoric? What reforms have actually been made? Who is gaining, and who is losing?

Thomas Sankara once said, “You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness.” That madness was visible in the streets of Ouagadougou in 2014. But a decade later, the question is whether that change has been realized—or whether it has been transformed into myth, a narrative that empowers the powerful while pacifying the people.

Burkina Faso’s insurgent grammar has not disappeared—it has been absorbed. Today, revolutionary slogans serve the very power structures they once opposed.

The constitutional coup

In 2014, Burkina Faso erupted into protest. What began as resistance to a proposed constitutional amendment became a sweeping rejection of Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year rule. At the time, I described the moment not merely as a revolution, but as a constitutional coup—a nonviolent seizure of political authorship by the people, and particularly by Burkinabè youth.

The proposed amendment to remove presidential term limits was only the trigger. Beneath it lay years of exclusion, generational frustration, and the systematic erasure of youth from formal governance structures. This uprising did not merely demand leadership change. It demanded symbolic, political, and epistemic recognition. It challenged not only the permanence of power, but the grammar through which power had been historically justified.

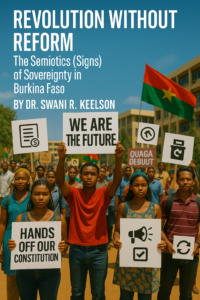

Protest slogans such as “Hands off our constitution” and “We are the future” weren’t just rhetorical flourishes. They marked a collective rejection of political invisibility. This moment was about authorship: the demand by a generation to redefine sovereignty—not as something inherited, but as something made, spoken, and re-authored in the streets.

Relative deprivation and the uprising

At the core of the 2014 uprising was what political theorists call relative deprivation—the deep frustration that arises when people feel they are entitled to more than they’re receiving, especially when expectations are high. For Burkina Faso’s youth—who make up the majority of the population—expectations had shifted. They were globally connected, politically conscious, and socially organized.

But their lived reality was one of unemployment, marginalization, and exclusion from decision-making. This dissonance produced not only anger—it produced rupture. The revolution was as much about dignity as it was about democracy.

The semiotics of resistance (signs)

The 2014 uprising was not just a political confrontation—it was also a revolt against the visual and symbolic language of state power. Semiotics, or the study of how meaning is created through signs and symbols, helps us understand the deeper currents of this resistance.

Burkinabè citizens rejected not only Compaoré’s rule, but the imagery and rituals that sustained it: the uniforms, parades, slogans, and visual displays that legitimized state authority. Protesters reclaimed these codes of power. Military fatigues—once symbols of repression—were worn by demonstrators as emblems of liberation. The long-silenced image of Thomas Sankara, the assassinated former leader, re-emerged on T-shirts, graffiti walls, and social media—not as nostalgia, but as defiance.

Even hashtags and chants became tools of authorship. Slogans like “Too young to remember another president” and “Hands off our constitution” did more than express protest—they performed it. They redrew the boundary between ruler and ruled, legitimacy and resistance.

This “insurgent grammar”—the use of language, imagery, and visibility to assert political presence—was a generational act of redefinition. Through words, attire, murals, and memes, a new claim to sovereignty was being made.

From protest to presidency

Nearly a decade later, the language of that insurgency echoes from the very platforms it once opposed. President Ibrahim Traoré—like his predecessor from the transitional period—publicly aligns himself with Sankarist symbolism. He wears military fatigues, speaks in the idioms of anti-imperial defiance, and has fostered partnerships with non-Western actors like Russia and Turkey. The mausoleum of Thomas Sankara has been renovated and rededicated under his regime. On the surface, these gestures suggest continuity with revolutionary ideals.

But what has emerged is not insurgent governance—it is symbolic continuity without structural change. The slogans of 2014 are now part of the state’s branding. The murals of protest have been institutionalized. What once disrupted the state now decorates it.

Traoré’s government performs revolution while consolidating power. Youth inclusion remains rhetorical. Decision-making remains opaque. Journalists are detained, civil society is constrained, critics are silenced. The very signs that once contested the regime now authorize it. What has occurred is not political fulfillment—but semiotic reversal.

The semiotics of sovereignty

In many postcolonial African states, sovereignty is often asserted through symbols before it is realized through governance. The performance of autonomy—via flags, alliances, military attire, and revolutionary slogans—frequently stands in for actual reform.

Burkina Faso’s expulsion of French forces and embrace of new global partners suggests a desire for decolonial sovereignty. But these symbolic actions occur amid internal contradictions: vast regions outside state control, continued extremist violence, and more than 6.5 million people in need of humanitarian aid. A state may declare itself sovereign through posture and rhetoric. But unless sovereignty is experienced through inclusion, redistribution, and accountability, it remains only a sign.

This is where semiotics—the analysis of how meaning is produced—remains essential. The regime’s anti-colonial displays operate through what I call discursive substitution: the replacement of substantive change with rhetorical continuity. The language of revolution is retained, but its meaning is inverted to justify new forms of control.

Discursive substitution and structural inertia

Burkina Faso’s current regime has not erased the revolution. It has absorbed it. This is not absence—it is appropriation. The language of rupture survives, but it has been hollowed out. Slogans of protest have become campaign tools. Sankara’s image hovers over institutions whose power remains unchecked.

This inversion is not accidental. It is strategic. It allows the regime to cloak itself in revolutionary legitimacy while avoiding revolutionary demands. Military uniforms now signal sovereignty, not resistance. Youth participation is invoked as rhetoric, not policy. Sovereignty is performed—but not shared.

What emerges is a symbolic regime: one that rules not only through institutions, but through imagery, slogans, and strategic appropriation. The semiotics of sovereignty has replaced its practice. But language alone cannot govern. And symbols alone cannot reconstruct legitimacy.

When symbols supplant reform

Burkina Faso is not alone. Across West Africa—from Mali to Sudan to Guinea—the appropriation of revolutionary language has become a tool of governance. But symbolic sovereignty is not a substitute for structural transformation. A revolution invoked but not enacted is not continuity—it is contradiction. And where redistribution does not follow rupture, the legitimacy claimed through slogans may eventually be contested not in language, but in uprising.

The post Revolution without Reform: The Semiotics of Sovereignty in Burkina Faso appeared first on African Arguments.